OPINION: Free speech zones and the struggle for freedom of expression

It is election season, and many students are asking: Why vote?

In 2008, voter turnout for 18-24 year olds reached a high of 49 percent, and many analysts predict this number to return to a more lackadaisical norm for 2012. While colleges are often considered the bastions of liberal arts and free speech, the condensing of First Amendment rights to a “free speech zone” on campus have hindered, rather than encouraged, civic engagement.

A recent editorial in the New York Times looked at this connection between youth voter apathy and the civic engagement of college campuses, concluding that institutions are too restrictive in their codification of First Amendment rights. Examples include Christopher Newport University, which banned students from protesting the arrival of Paul Ryan on campus for failing to correctly apply for a permit of demonstration in a “free speech zone.” The University expects students to apply ten days in advance, and Mr. Ryan’s visit was announced two days before his visit. In another example, a federal judge recently struck down the University of Cincinnati’s “free speech zone,” arguing that limiting free speech to 0.1 percent of campus was too restrictive. In both of these cases, institutions attempted to limit students to a confined “free speech zone,” which both limit the space of students’ expression and can require bureaucrat hurdles to book

In the 1969 case Tinker v. Des Moines, the Supreme Court famously concluded that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” While applied specifically to high school students protesting the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands, the case set a precedent for all public institutions of learning in the United States that those rights afforded by the First Amendment to any American in public space are dually granted to students attending public schools.

One important limitation of this right is that one’s exercising of free speech cannot impede the normal flow of the business of an institution. While this can easily be abused, it protects teachers from students interrupting classrooms, administrators from protesters that might disrupt their work, and students from passionate voter registration volunteers while walking to class. In this way, the expectation is for institutions to articulate where speech is specifically prohibited, rather than where it is specifically permitted.

Thus, this equal extension of rights, whereby one’s ability to demonstrate on the National Mall is equal to one’s ability to protest in a university’s quad, begs the question: What is a “free speech zone”? If an area of a university is open to the public, and protesting there does not disrupt the normal flow of the university, does this space become a “free speech zone”? Or is it a symbolic gesture to suggest that the entire institution, so conducive to liberal arts and free-thinking, is a “free speech zone”? I remain confused as to why, when a university’s goal is to inspire civic engagement, universities might limit these actions to a particular “zone.”

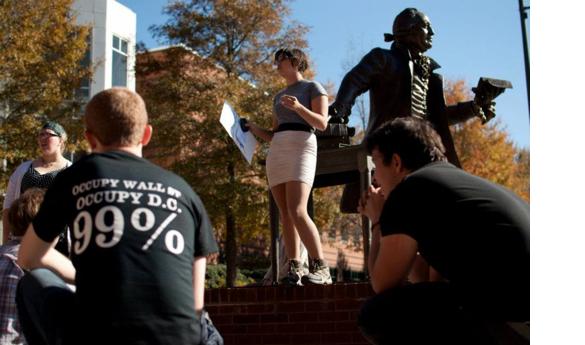

At George Mason University, we do a bit of a two step: we are much more open and innovative when it comes to tolerating free speech, yet take several small steps that appear to discourage free expression. As a student, I am proud that we allow preachers to come onto campus to spout diatribes and vitriolic messages. At the same time, I have often heard North Plaza called a “free speech zone”; while I admire the symbolism, I would hope this nomenclature does not develop to a prohibition of protests outside of this area.

In addition to this particular area, a distinction exists between free expression on campus and in residence life. For example, students are allowed to smoke hookahs next to the JC, but not in the middle of President’s Park. This duplicitous application suggests that the latter is not a protection for fire safety, but a prohibition of “marijuana paraphernalia.” Housing’s ban on “drug paraphernalia,” such as forbidding the use of hookahs, represents a First Amendment infringement by the university. This example extends to any paraphernalia banned in the residence halls, including posters and artwork that incorporate marijuana and alcohol.

With the election coming up, with higher education making a brief headline in the debates, and the student debt crisis continuing to burden students, all eyes will be on the voter turnout for college-age students. In order to increase these turnout numbers and encourage politicians to act on these issues, George Mason University and other institutions should take steps to avoid the containment of the First Amendment to “free speech zones.”

Opinions expressed in this column are solely the beliefs of the writer.

Would you like to have your opinion considered for publication? If so, send an email to opinion@connect2mason.com with the subject line "opinion writer position."