Documentary chronicles life and death of journalists in Mexico

In 2012, approximately 232 journalists were imprisoned worldwide according to The Committee to Protect Journalists. This statistic marked 2012 as one of the toughest years for journalists. Each day, the people in this profession risk their lives to tell stories while facing possible imprisonment, torture or death.

Yet, journalists continue to do the difficult work of telling the story; but, if the work is so risky, why do journalists continue to risk their own lives?

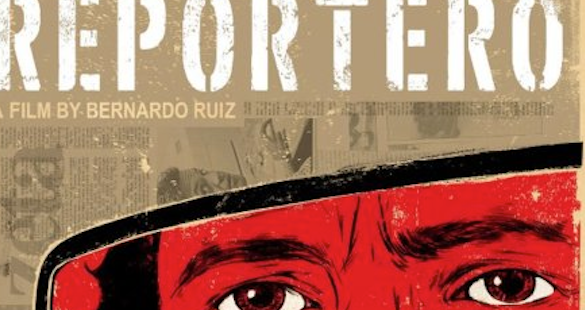

That question is asked time and time again in the 2012 documentary “Reportero,” which will be screened at George Mason University’s Fairfax campus as part of the film and media studies department’s ongoing Visiting Filmmakers Series.

“Reportero” focuses on the ongoing conflict between journalists in Mexico and the current drug war involving the Mexican drug cartel. Citizens and journalists are constantly living in a state of fear in a place where homicides occur daily; individuals are afraid of the unpredictability of when the next attack will happen. It is a state of fear that is difficult for most Americans to fully grasp. This fearful state and the actions taken by journalists to expose organized crime by the drug cartel is what “Reportero” is all about.

|

| "Reportero" director Bernardo Ruiz began research on his film back in 2007 (photo courtesty of Quiet Pictures). |

Director Bernardo Ruiz spent five years working on the film, beginning in 2007 with the initial research. Yet, when he visited the United States-Mexico border, he had no intention of making a film about journalists.

Instead, he came to the border to focus on the stories of children who had been deported at a shelter; however, his initial focus quickly shifted to the journalists at the center of the drug war through a chance meeting with 30-year veteran reporter, Sergio Haro.

“The film really is about Sergio and his colleagues,” said Ruiz in a recent interview with Connect2Mason. “It’s really the story of a reporter and a newspaper that are under siege.”

It is easy to classify Sergio as the protagonist in the documentary. As a journalist, who himself has received death threats by the drug cartel, Sergio continues to tell the stories behind the body counts.

“He’s after the story behind the story,” Ruiz said. “He’s not interested in telling you about a specific gun battle on a specific street, but instead the bigger forces at play,” such as the husbands, wives, sisters, brothers, and the community continuously affected by organized crime.

“Sergio is interested in telling the human story, in the crack—how lives are impacted by this situation,” Ruiz continued.

In parallel, “Reportero” also centers on Zeta, a weekly newspaper in Tijuana, Mexico that, in the 30 years of its existence, has been plagued by numerous death threats against its own journalists and editors. In some cases, these death threats have resulted in the actual death of Zeta journalists.

At the newspaper, the fearsome editor Adela Navarro has continued to be a strong editor and has not been shy about where Zeta’s opinions lie.

The weekly newspaper isn’t afraid to expose the crimes of the drug cartel and have been staunch anti-supporters of the cartel. Ruiz sees Zeta and Navarro as a force to be reckoned with in dealing with the drug cartel.

“They wear their perspectives on their sleeves, and Adela has been at the forefront of that by pushing her reporters to do even more aggressive coverage of organized crime,” said Ruiz after having spent a great amount of time with Navarro and at Zeta.

A turning point in the drug war occured during the 2006 election of Mexican President Felipe Calderón, as he took a strong stance against the drug cartel and organized crime in Mexico following his win.

However, Calderón’s win wasn’t seen by many as legitimate. To reinforece his win, Calderón began to make bold moves towards confronting organized crime groups. Using an unequipped Mexican military to combat these groups, Calderón focused on short-term actions rather than long-term systematic ones to combat the actual problem.

Calderón’s actions have been viewed as rash resulting in more crime, with members of the cartel growing in regional and economic power throughout the country.

“The drug economy is more complex than just fighting off the ‘bad guys’,” Ruiz said. “Strengthening the judicial system and the civil society is a better alternative.”

What Calderón failed to do is focus on fixing the judicial system or the corrupt government by focusing on ways to see direct results, without long-term solutions.

Exposing the anonymity of the drug cartels has been the main reason why journalists at Zeta and across Mexico have been threatened and targeted. Cartels are used to operating under the mask of a hidden identity, enabling their members to live double-lives despite their crimes.

In 2004, Zeta Founder and Editor Francisco Javier Ortiz Franco was gunned down because he allowed the publication of the names and faces of drug cartel members, individuals who had been enjoying anonymity in Tijuana while being a part of organized crime. This situation is just one of the many threats and stories that are results of Zeta’s fearsome investigative reporting to break the barrier between what journalists should or should not be doing in Mexico.

“You don’t oust the criminals because it’s perceived as a threat to business or an actual threat to business in such a high risk situation,” Ruiz said.

Attacks on journalists, as documented in “Reportero,” are a result of the climate of fear that can be more threatening than an actual gun shot. The unpredictable atmosphere continues to place these journalists and editors in a prolonged game of waiting for the next series of attacks.

Journalism is like any job: you have to keep doing it; you can’t just stop doing your work. Yet, it is the courageous journalists who continue to expose government corruption, organized crime and more, despite their lives being threatened.

However, journalists are often criticized for not doing enough.

“One of the journalists I spoke with said, ‘Hey, we’re not marauders. We’re not trying to be heroes. We’re just people trying to do our jobs. Our job is to report on the stories unfolding here.’ And then it’s up to civil society to do something,” Ruiz said. “We can’t expect journalists to do everything. Their job is to get the story out there, get it right; and what happens with that information is up to civil society.”

“It’s really a story about how people who have been laboring invisibly in the region and why they continue to do this difficult work,” Ruiz said.

Much like the drug cartels themselves, the journalists covering this issue work under a shield of anonymity. They have to remain almost unknown in order for their lives to not be threatened. Yet, these journalists take personal ricks to uncover the mask of organized crime, with a threat of their own name being ousted.

The film screening of “Reportero” was originally scheduled to be screened on Wednesday, March 6 at 4:30 p.m. in the Johnson Center Cinema followed by a Q&A discussion with Director Bernardo Ruiz. However, due to inclement weather, the film screening is set to be rescheduled.

The film and media studies department will be updating their website once a new screening date has been scheduled.

Update for April 7, 2013: The film screening of "Reportero," along with a Q&A with director Ruiz will be held on Wednesday, April 10 at 6 p.m. in Mason Hall's Meese Conference Center.