Shrinking support raises questions about higher education funding priorities in Virginia

Compared to older state universities, Mason receives the least funding per-student than any other public doctoral institution in Virginia. As less and less of Mason’s budget is supported by state funds, questions are raised about how the Commonwealth supports higher education.

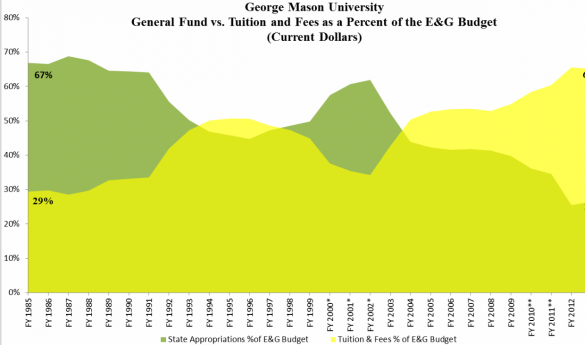

At a budget forum in the fall of 2013, Provost Peter Stearns presented a graph to the audience that showed an ominous decline in state support of George Mason University. Since 2003, the percentage of state-supported spending on instruction and other educational costs at Mason dropped from 53 percent to 26 percent in ten years.

“We don’t really expect to start reversing the trend even if the economic times improve,” Stearns said at the time. “So this is a significant change.”

As state support decreased, Mason’s educational costs, commonly referred to as the Educational & General Budget, more than doubled, from $196 million in 2001 to $416 million in 2011.

“When enrollment goes up, we spread money to the academic units and, where possible, non-academic units to compensate for the increased activity,” Stearns said. “If the enrollment growth is substantial, it’ll make up most of the change.”

Mason’s student FTE (or full time equivalent, which accounts for part-time students) jumped from 19,000 in 2003 to 24,000 in 2012, a 26 percent increase. When accounting for part-time students, Mason is the third-largest school among Virginia’s four-year public universities, falling only behind Virginia Tech and Virginia Commonwealth University. According to the State Council of Higher Education, Mason is expected to have the second-highest number of FTE students among state public institutions by the 2016 school year.

|

| Mason receives the least funding per-student among all Virginia doctoral schools (data provided by Mason Institutional Research & Reporting). |

While enrollment growth has put strain on the E&G budget, Mason continues to have the lowest per-student support from the state. Over the past ten years, Mason received the lowest amount of state support per student than any other doctoral institution in Virginia. In 2013, the University of Virginia received the most at $8,334 per student, followed by the College of William & Mary at $7,300. Mason received $5,291.

Many Mason officials question why the university receives less state support than schools like UVA or William & Mary, and point to the state’s higher education funding process as part of the problem.

How Virginia funds higher education

Compared to Mason, Virginia’s more historical institutions like UVA and William & Mary grew relatively little over the last ten years. UVA gained three thousand students between 2001 and 2011, while William & Mary gained six hundred. Over that same period, Mason’s FTE count jumped by eight thousand students. Virginia Commonwealth University jumped nine thousand.

“If you look at schools that have been around the longest…they typically have higher funding levels,” said Tom Kramer, executive director of Virginia21, an advocacy group that represents college-aged students. “In a lot of ways, George Mason is absorbing the brunt of a lot of demands, but a lot of the funding is not following those demands.”

Unlike most states, Virginia does not have a strict set of guidelines for how universities receive funding. This puts strain on schools like Mason that are expanding to serve a greater number of students. According to university administrators and others involved in state higher education, the process is determined, in part, by informal ties to the state.

“We don’t have the historic relationship [with the state],” Stearns said. “To be candid, I think there is something of a historic bias towards Northern Virginia.”

This opinion is shared by non-university officials, as well.

“I think newer universities, like George Mason, until more recently didn’t have the relationships with state budget makers that are instrumental in helping to get projects & funding,” said Delegate David Bulova, whose district partly encompasses Mason’s Fairfax campus and who sits on the higher education subcommittee in the Virginia House of Delegates.

Schools like Mason, who have expanded enrollment to serve an increasing demand for college degrees, do not receive as much funding for doing so.

“Some of the newer schools, what they suffer from the most…they’re observing the brunt of the demands for higher education,” Kramer said. “Legally, there is no such thing as per student funding. We just don’t allocate money per student.”

Even so, Virginia public universities are fighting over a diminishing amount of available state funds.

“Virginia is what’s considered a low tax state. If you look at the overall state budget, about 90% is already locked in,” said Mark Smith, director of state government relations at George Mason University. “When it comes down to discretionary funding there is only about 10 percent for the government to shift around for all of those other priorities that might be out there.”

According to Stearns, competition over state funds is becoming more difficult as an increasing amount of the state’s budget is spent on other programs – most prominently rising Medicaid and Medicare costs.

How Mason is responding to declining state support

As the state fails to pick up support for increasing enrollment, a larger amount of the financial burden is shifted to students. To compensate for the drop in general fund support, Mason has increased tuition to pick up the slack.

According to a report by the Joint Legislative Audit & Review Commission, an oversight agency of the state general assembly, Virginia as a whole has increasingly shifted the financial burden of higher education to students.

“This reduction in State support has coincided with students providing a higher portion of institutional revenue through tuition and fees,” read the report. “Virginia’s public four-year higher education institutions derived, on average, 23 percent of their total revenue from tuition and fees paid by students in 2011, up from 16 percent in 1991.”

At Mason, rising tuition costs have largely coincided with decreasing state support. In 2003, tuition & fees and state funds comprised of about the same percentage of the E&G budget. Today, tuition accounts for 69 percent of the budget, while 28 percent is supported by the state.

This has particularly adverse effect on Mason students, about 56 percent of who subsidize at least a part of their higher education costs with debt. As Kramer says, this would be less of a problem at schools like UVA or William & Mary, whose students don’t rely as much on loans or grants. Only 30 percent of UVA students use student loans.

“If GMU raises tuition…they’re basically raising debt money,” Kramer said. “If UVA can raise its tuition to make the new money, it aught to just raise tuition. Schools that have a higher percentage of first generation college kids…that’s where the state should prioritize funding based on need.”

Even in the last few years, Mason saw a rapid increase in enrollment of under-represented groups. An additional 2,000 economically disadvantaged students enrolled in 2013 than they did in 2009.

The difficulty with funding by performance measures

Higher education officials like Stearns would like to see a more stable funding process come from the state.

“It would be very helpful of the state to be more consistent about their decisions about performance standards,” Stearns said. “We will be making our decisions increasingly on grounds of other revenue sources.”

The problem lies in which performance measures the state should emphasize when deciding how to appropriate funds.

“You have to make formulas that work for everyone,” Kramer said. “What is going to provide the carrot that [the University of Mary Washington] responds to that [George Mason University] also responds to? How do we make sure we’re not hurting good colleges? You don’t want to turn UMW and William & Mary into a large state school…that kills their mission.”

Mason would benefit from a funding process that rewarded enrollment growth, but would still fall behind if the state put more emphasis on four-year graduation rates, a metric that benefits more traditionally-structured schools like UVA and William & Mary.

“I would also say that there are winners and losers depending on the institutions that are out there,” Smith said.

Some say that while the state is a long way from setting the guidelines, progress is being made.

In 2011, the General Assembly passed the Higher Education Opportunity Act, which was meant to overhaul the funding formula by holding public universities to a new set of performance measures.

The bill is meant to provide a stable financing system to support the demand for a more educated workforce. As the bill reads:

“The objective of this [bill] is to fuel strong economic growth in the Commonwealth and prepare Virginians for the top job opportunities in the knowledge-driven economy of the 21st century by establishing a long-term commitment, policy, and framework for sustained investment and innovation that will enable the Commonwealth to build upon the strengths of its excellent higher education system and achieve national and international leadership in college degree attainment and personal income, and that will ensure these educational and economic opportunities are accessible and affordable for all capable and committed Virginia students.”

Though the 2011 act proposes broad metrics for how higher education institutions should be supported, it does not make any specific rules for doing so.

“The act sets up a framework…and an agreement for additional flexibility,” Bulova said. “You want to develop a system that is inherently flexible, otherwise you run into the problem that the act was trying to solve.”

One of the bill’s more ambitious goals is to produce 100,000 cumulative additional undergraduate degrees in Virginia by 2025; a goal that would put additional pressure on schools to increase enrollment.

According to Kramer, coming up with the money to support the performance-based measures is one of the key roadblocks to achieving the bill’s goals.

“Without the money, the act won't work,” Kramer said. “If a school like Mason accepts more people into the school than there is funding to distribute per student, funding goes down and everyone's tuition needs to go up to ensure the same level of quality for all students.”

According to the university’s six-year plan for 2012 through 2018, Mason projected enrollment growth and performance measures will have to be supported by state funds.

“…George Mason’s plan includes $2,168,000 in general funds to support our projected enrollment growth,” read the plan’s description. “Our deliberate inclusion of these funds reflects the unequivocal need for additional support to carry out the university’s and the Commonwealth’s shared goals in this area.”

Until then Mason will continue to look at other sources of revenue to make up for a growing E&G budget.

“We make our basic enrollment decisions largely on grounds other than state requests,” Stearns said. “We’ll try to grow with a mix of out-of-state and in-state students.”

Follow Frank on Twitter @FrankMuraca, or email him at fmuraca@gmu.edu.